A week in Bangkok offered a powerful glimpse into Asia’s diverse democratic struggles—from performative democracy and migration justice to Gen Z movements and transformative masculinities. Inspired to bring new ideas back to Korea.

Last week, I attended the Asia Democracy Assembly held in Bangkok, Thailand. It was a truly special time spent with activists from across Asia who are fighting for democracy.

Given the major political crisis Korea experienced last year and this year, I was curious to see how the Korean case would be addressed at the event. But with so many countries in Asia facing far more severe situations, it was difficult for Korea’s case to take center stage. Still, whenever I found the chance, I shared updates on the situation in Korea and stories from the square with fellow democracy activists.

One of the most striking concepts from the official sessions was “performative democracy.” Inspired by the idea of performative masculinity, it describes political actors who use the language of democracy on the surface, while hollowing out actual citizen participation and equality in practice. The discussion on going beyond this—toward a democracy that is felt and lived in everyday life—stayed with me. It reaffirmed that the future tasks of Asian democracies lie not only in institutional or procedural reforms, but also in improving people’s real, lived experiences of democracy.

I also appreciated the attempt to conceptualize democracy not merely as a procedural system, but as something that must encompass diverse genders, races, migration backgrounds, and minority identities. It was encouraging to see efforts to broaden the horizon of democratic discourse in such an inclusive direction. This affirmed once again that an inclusive democracy is the right direction for the international community and for democratic discussions moving forward.

In that sense, the session on migration was also impressive. Considering that roughly 40% of all migrants in the world are in Asia, it is time for Asian countries to take a leading role in addressing the issue of “people on the move.” Much of Asia is already facing severe population aging and growing dependence on migrant labor, while far-right anti-immigrant sentiment is also spreading. This raises urgent questions about what this means for those of us living in Asia, and how Asian countries should provide standards and leadership to the international community. This, I felt, is truly an Asian democratic and human rights task—one that defends the minimum standards of rights and humanity.

Given the importance of minority issues, the role of national human rights institutions (NHRIs) is also crucial in upholding these minimum standards. One session explored the current state of NHRIs across Asian countries and discussed possible alternatives. I was surprised to learn how often NHRIs fail to adequately respond to major human rights violations in their own countries—even where such commissions exist. It reminded me of how the National Human Rights Commission of Korea failed to act meaningfully under the recent emergency decree. One Korean panelist noted that restoring the function of Korea’s NHRI could contribute to strengthening human rights across Asia as well—an argument that left a deep impression on me. It is time to gather strength so that the National Human Rights Commission of Korea can redefine and reform its role.

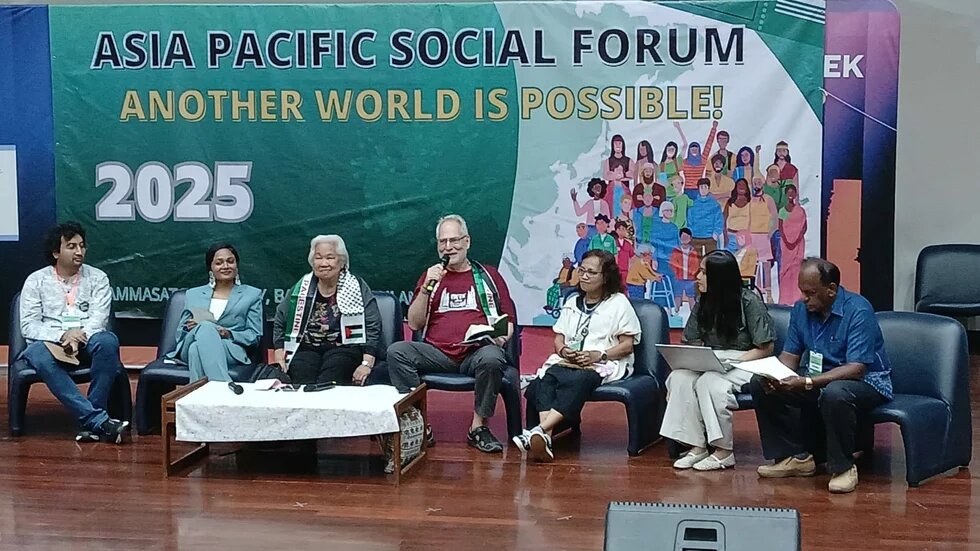

On my day off, I happened to join the social movement session at the Asia Pacific Social Forum. Many of today’s democracy movements across Asia are being led by younger generations, and this trend is being described as the “Gen Z Movement.” One of the key questions was: how can these new, horizontal, digitally rooted movements sustain themselves over time? This overlaps with the questions raised in the book The Paradox of the Square that I recently read. I hope discussions on sustaining civic participation after large-scale square movements will also take place more vigorously in Korea.

Another interesting analysis was how economic inequality and labor precarity have shaped solidarity among young people and informal workers across Asia. This, too, seems like an essential discussion for Korea after the square.

Lastly, I want to mention the Asia Masculinities session, which was proactively organized by Korea’s “Feminism with Him” team. As “runaway masculinity” becomes a major social issue alongside the rise of the far right, it is increasingly important to identify examples of alternative masculinities, propose new models, and imagine new forms of solidarity. In this context, one of the activists from Japan presented Japanese politician Manabu Terada as an example of transformative masculinity. He paused his political career to support his wife’s political work and took on full-time childcare responsibilities. He believes that caring for his child will empower him to care for his country as well. We need to cultivate such alternative masculinities—citizens who do not remain silent, but participate in change—and work alongside them as allies.

This journey allowed me to feel, with my whole body, the diversity of Asian democracies and the possibilities of solidarity. I hope this experience will help spark new imagination and new forms of practice back home in Korea.