South Korea has seen has a notable progress in gender and human rights over the past two decades. Yet, in recent years, political polarization, anti-gender backlash, and stalled legislative efforts have complicated the landscape, leading to a fragmented and contested approach to equality and inclusion.

Erosion of Gender Equality and Rise of Anti-Gender Movements

Legal reforms during the 1990s and 2000s advanced gender equality, including protections against workplace discrimination and gender-based violence (Kim & Roh, 2016). However, younger men—particularly in their 20s and 30s—began to view these efforts as undermining their own standing in a highly competitive society.

By the late 2010s, alongside South Korea’s #MeToo movement—ignited by a female prosecutor’s public testimony of workplace sexual harassment—the country also witnessed a sharp rise in online sexual abuse cases. One of the most notorious was the Telegram Nth Room case, in which perpetrators illegally obtained and distributed sexually exploitative and violent images of women through online messaging platforms for profit (Human Rights Watch, 2020). While these incidents galvanized widespread public support for feminist movements, they also triggered strong backlash from right-wing media and online communities that portrayed gender equality efforts as divisive and excessive.

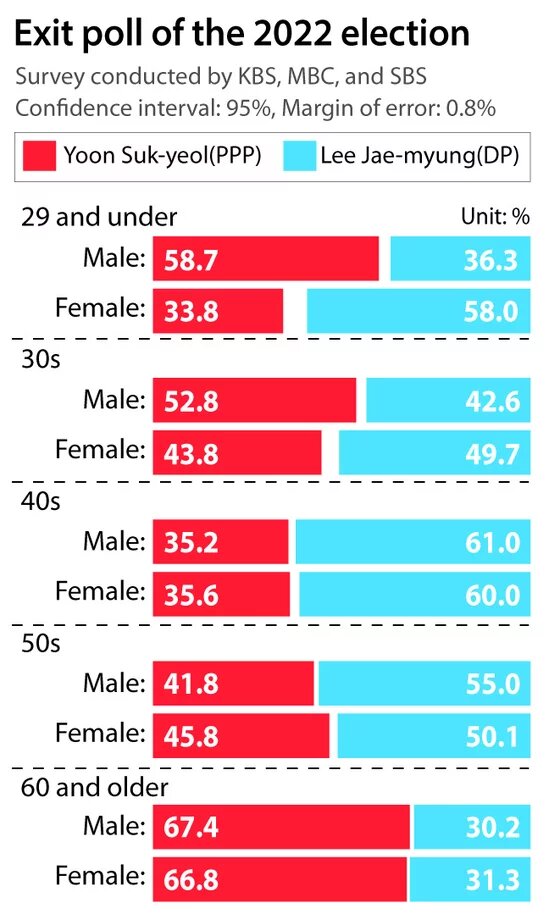

During the 2022 presidential election, candidate Yoon Suk Yul denied the existence of structural gender inequality and promised to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (Gunia, 2022). His platform struck a chord with conservative voters and disillusioned young men in their 20s—58% of whom supported Yoon, contributing significantly to his victory (Lee, 2024). Since taking office, gender-focused programs have faced defunding, rebranding, or cancellation, reflecting a broader political trend that frames gender rights as a cultural battleground rather than a fundamental human rights issue.

Stalled Anti-Discrimination Legislation

Despite multiple legislative attempts since 2007, South Korea has yet to pass a Comprehensive Anti-Discrimination Act. The proposed bill seeks to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics, disability, race, age, religion, and other statuses. Advocacy from civil society, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, and international human rights bodies has been persistent, yet insufficient to overcome entrenched political resistance (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

The main source of opposition comes from conservative religious groups and right-wing public figures, who frame the bill as promoting so-called “LGBTQIA+ propaganda” and violating religious freedom (Park, 2020). Even within liberal parties, lawmakers have hesitated to support the bill due to fear of electoral repercussions. As a result, there still is no comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation and it leaves many marginalized groups without adequate legal protection.

Abortion: Legalized but Unregulated

The Constitutional Court's 2019 decision to decriminalize abortion—effective January 1, 2021—was a landmark moment in South Korea’s reproductive rights history. However, the lack of follow-up legislation has created a legal and procedural vacuum. Medical providers face ambiguity around service provision, and individuals seeking abortion services encounter inconsistent access, high costs, and limited support (Yoon, 2024).

Civil society groups have responded by calling for a comprehensive reproductive rights framework. Their demands include public health insurance coverage, legal protections for bodily autonomy, and the incorporation of reproductive self-determination into health policy. While the Ministry of Health has begun drafting regulations to approve abortion pills, as of early 2025, no pharmaceutical options are yet fully authorized or regulated (Jung, 2024).

Sex Education: Inadequate and Exclusionary

Sex education in South Korea is part of the national school curriculum but remains heavily criticized. Current programs are predominantly abstinence-based, lack up-to-date information on contraception and STIs, exclude content related to sexual orientation and gender identity, and reinforce binary gender norms. These shortcomings fail to meet the evolving needs of young people (UNESCO, 2023).

Attempts to modernize sex education have faced pushback from religious and parental groups, who label reforms as promoting LGBTQIA+ and pro-choice agendas (Lee, 2022). In response, civil society is pushing for Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), which promotes a rights-based, inclusive, and evidence-based approach to sexual and reproductive health. Without such reforms, young people remain vulnerable to misinformation and harmful stereotypes (UNESCO, 2023).

Marriage Equality: Legal Recognition Remains Elusive

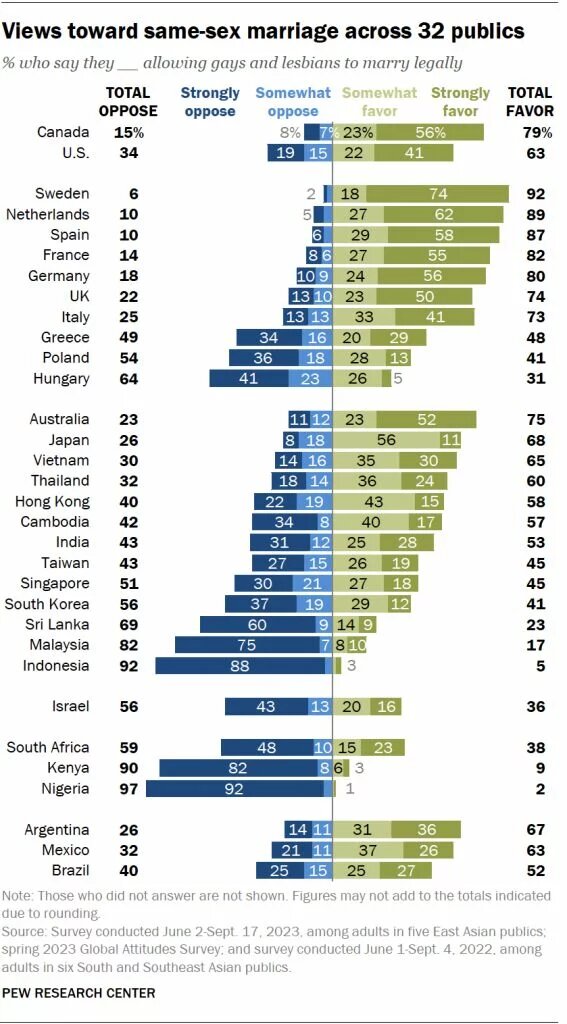

While South Korea’s Constitution does not explicitly ban same-sex marriage, such unions remain legally unrecognized, denying LGBTQIA+ couples basic rights like spousal benefits and inheritance. The issue gained visibility in 2013 when filmmaker Kim-Jho Gwangsoo held a public same-sex wedding, drawing national attention to the lack of legal protections (Chung, 2013). Momentum grew following a 2023 Seoul High Court ruling that sided with a same-sex couple denied spousal health insurance—marking a symbolic but limited victory (Yim & Shin, 2024). Marriage for All Korea (MAK), a key advocacy coalition, continues to push for reform through litigation and public campaigns.

Public support is rising, especially among younger generations, with 61% of people aged between 18 and 34 favoring marriage equality (Pew Research Center, 2023). Still, political resistance remains strong, with no major party backing legalization amid pressure from conservative and religious groups.

Conclusion

South Korea stands at a crossroads in its human rights journey. While past reforms created momentum for gender and sexual equality, the current political climate has stalled or reversed progress. The rollback of gender equality policies, resistance to anti-discrimination legislation, and lack of legal recognition for same-sex relationships all point to a need for renewed, sustained advocacy.

Civil society continues to play a vital role in advancing rights-based frameworks, pushing for comprehensive legislation, inclusive education, and institutional protections. However, meaningful change will require not only advocacy but also political courage and a broader societal commitment to human rights and social justice for all.

Reference

Kim, E.-S., & Roh, J. (2016, September 30). The future of gender and women’s activism in Asia. Global Asia, 11(3)

Human Rights Watch. (2020, March 27). South Korea: Online sexual abuse case illustrates gaps in government response. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/27/south-korea-online-sexual-abuse-case-illustrates-gaps-government-response

Gunia, A. (2022, March 10). How South Korea’s Yoon Suk-yeol capitalized on anti-feminist backlash to win the presidency. TIME. https://time.com/6156537/south-korea-president-yoon-suk-yeol-sexism

Lee, B.-j. (2024, September 25). Gen Z's growing gender gap. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/article/3843431

Human Rights Watch. (2021, November 11). National Assembly of South Korea should act swiftly to enact anti-discrimination legislation. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/11/11/national-assembly-south-korea-should-act-swiftly-enact-anti-discrimination

Park, J. (2020, August 14). Conservative Protestant churches vow to stop passage of anti-discrimination law. The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/12/113_294309.html

Yoon, S.-Y. (2024, July 7). ‘No update since 2019’: Korea’s inaction on abortion issue leaves women in limbo. Korea JoongAng Daily. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2024-07-07/culture/features/No-update-since-2019-Koreas-inaction-on-abortion-issue-leaves-women-in-limbo-/2084041

Jung, M. (2024, July 22). Exclusive: Korea drafting bill to grant access to abortion pills. The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/amp/southkorea/health/20240722/exclusive-korea-working-on-bill-to-grant-access-to-abortion-pills

UNESCO. (2023, July 7). Republic of Korea | Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Education Profiles. https://education-profiles.org/eastern-and-south-eastern-asia/republic-of-korea/~comprehensive-sexuality-education

Lee, S. (2022, July 7). Sex education in Korea still stuck in the past. The Hankyoreh. https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/1073604.html

UNESCO. (2023). Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) Country Profiles. Global Education Monitoring Report.

Chung, J. (2013, September 7). Gay South Korean film director marries his partner in public. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/lifestyle/gay-south-korean-film-director-marries-his-partner-in-public-idUSBRE9860B3/

Yim, H., & Shin, H. (2024, July 18). In landmark ruling, South Korea's top court confirms state benefits for gay couples. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-koreas-top-court-upholds-landmark-ruling-over-same-sex-spousal-state-2024-07-18/

Pew Research Center. (2023, November 27). How people around the world view same-sex marriage. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/27/how-people-around-the-world-view-same-sex-marriage/