On December 3, 2024, President Yoon Suk-yeol’s declaration of martial law dealt a profound shock to South Korean democracy. Yet in that moment of crisis, the square came alive once again—and at its center stood the youth. The lights, the flags, and the questions that followed have now been captured in a book. After the Square tells the story of young people who organized themselves to call for President Yoon’s resignation, created spaces for public dialogue, and put democratic values into action. We spoke with one of the book’s co-authors, Jaejeong Lee.

Ⓒ Provided by YoonToiCheong (Youth for Yoon’s Resignation)

Source: Sisa Journal (www.sisajournal.com)

1. Could you briefly introduce the book 'After the Square'?

After the Square is a book that raises critical questions about the state of democracy in South Korea following the December 3rd martial law crisis—a moment that sent shockwaves through Korean society.

While the public square seemed divided between those supporting and opposing the impeachment of President Yoon Suk-yeol, beneath the surface lay far more complex dynamics. This book examines the multifaceted political landscape shaped by class, gender, generation, and ideology, and explores the directions Korean society could take moving forward.

The book features contributions from four authors:

First, Professor Jinwook Shin (Department of Sociology, Chung-Ang University), who has long studied civil society and democracy, analyzes how democratic backsliding has unfolded in Korea and how far-right populist forces have gained ground. Second, I contribute as an early-career researcher focused on precarious labor and social policy, and as someone actively engaged in the square through various civic groups. I present an analysis of survey results collected from young participants in the protests. Third, Professor Seunghoon Yang (Kyungnam University, Sociology) investigates the social discourse surrounding the so-called “far-right shift” among young men in their 20s and 30s, and proposes a reframing of this narrative. Lastly, Professor Seungyoon Lee (Department of Social Welfare, Chung-Ang University), a specialist in labor field research, presents findings on the insecurity and class perceptions among today’s youth.

This book moves beyond narratives of hate, polarization, and generational conflict to uncover the diverse layers of civic life, asking where we must go next—and what we must collectively grapple with—to restore and renew democracy.

2. Now that the book is out in the world, what thoughts or emotions come to mind when you look back on the “square”?

When I think of the square, I remember the glittering lights I saw from atop the march truck, and the flags swaying in rhythm. Each light had a different hue, and each flag bore a different symbol—but together, they formed a collective brilliance in the face of a grave crisis. That image reminds me that the strength that overcame the martial law crisis came from the most ordinary people in Korean society.

While it was the so-called elites who triggered the crisis, it was the everyday people—those often marginalized and oppressed—who ultimately held society together. That’s why I continue working to collect and amplify their voices. I’ve been documenting the stories of those who came to the square, and organizing forums that evaluate the square and the presidential election not from the perspective of the older generation, but through the eyes of youth themselves. I hope the story of the square is remembered not as the legacy of any one figure, but as the sum of many acts of dedication, diverse narratives, and collective demands.

3. What kind of organization is “Youth Demanding Yoon Suk-yeol’s Resignation (YoonToiCheong),” the group that connects you with the square?

I have experience working in civic organizations, the National Assembly, and political parties. Even before the declaration of martial law, issues of government corruption under Yoon Suk-yeol’s administration were coming to light. This, along with the irresponsible responses to the Itaewon tragedy and the Cha Sang-byeong incident, reignited the accumulated anger among many of us. Around November 23, I proposed a “Youth Civic Declaration on the National Crisis” with friends who shared similar concerns, which marked the beginning of the Youth Demanding Yoon’s Resignation (YoonToiCheong) movement.

At first, I didn’t expect it to become an organized group; I thought it would just involve issuing and announcing the declaration. But on December 3, when President Yoon declared martial law, I felt that we could no longer stand by as democracy was being undermined. Starting December 4, we formed a working team, divided roles, and began organizing YoonToiCheong more systematically.

Currently, we are working to gather and preserve the voices of youth collected in the square. We also participate in exhibitions documenting the square’s events. Recently, we organized a forum where young participants evaluated the square and the presidential election from their own perspective. Above all, I believe it is crucial to carefully record the stories built together with citizens in the square so that they are not distorted or lost, and to transform these into a driving force for future activities. We continue to think about how to keep daily public discourse alive and how to maintain the communities formed in the square.

4. As a representative of various youth organizations, what has been the most challenging moment for you?

Living as a young person in Korean society is incredibly busy. There are many expectations placed on us—not only the pressures of exams and employment, but also the demands to be a good family member through marriage, filial duty, and more. Despite each person’s hectic daily life, young people gathered in YoonToiCheong with a shared desire to overcome the democratic crisis, contributing their time and resources. However, as the movement prolonged, many of us became deeply exhausted and worn out.

What I learned through that difficult period is that no one will do our work for us. When we feel a problem, we must define it ourselves, seek solutions, and find ways to act. If we expect someone else to do it for us, those expectations are rarely fulfilled. One of the most rewarding aspects of my work with YoonToiCheong was when, at a time when stories and stereotypes about youth from the square were rampant, we took it upon ourselves to document our voices by conducting surveys and recording our experiences. There’s a pride in having gathered voices that might have otherwise scattered. That record has become a valuable resource for pointing out societal issues in Korea and suggesting directions for moving forward.

5. Now that the new government is in power, to what extent do you think the voices from the square are being reflected in actual politics and policy?

The new government currently brands itself as a “people’s sovereignty government.” Seeing how the administration has increased engagement with citizens through regional town hall meetings and actively communicates with the media, I feel that democracy has been significantly restored and advanced compared to before.

However, there are still many disappointments when it comes to the agenda. In the square, there were many urgent calls for proactive measures against discrimination and hate, as well as for resolving economic inequality. Yet, in the actual policy realm, discussions around the Anti-Discrimination Act—a key policy to address discrimination and hate—have not progressed at all. There is also no discussion regarding diverse family structures. Additionally, with the expansion of precarious labor and social security systems failing to cover these workers, and the increasing number of unemployed youth, clear solutions have yet to be presented. Since it is still early in the administration’s term, I hope that effective policies will be introduced and many solutions proposed in the remaining period.

6. Many young people participated in the movement demanding Yoon Suk-yeol’s resignation as their first-ever protest. Since then, various civil society organizations have been trying to maintain connections with them. What efforts do you think civil society should make going forward to ensure that this participation does not remain a one-time event?

I believe there are two key directions to consider. First, it’s important to introduce young people—who have developed a strong sense of democratic citizenship—to the role of civil society activists as a new career path and to help them become colleagues in this field. Providing education that deepens their understanding of civil society organizations and linking them to hands-on activist experiences seems necessary. In fact, I’ve heard stories of citizens from the square becoming members of civil society groups they encountered there, joining labor unions, or even starting full-time activist work. Given the serious employment challenges young people face today, it’s important to raise awareness that full-time positions in civil society organizations can be legitimate jobs. At the same time, these organizations need to continuously reflect on and improve the working conditions and career prospects of activists, which have been chronic issues.

Second, I think it’s necessary to diversify the roles and methods that allow citizens to contribute to social change even if they are not full-time activists. I’ve met activists from the US, Europe, and Latin America, and while each organization has its own structure and system, many rely more on part-time or volunteer activists rather than full-time staff. Opportunities and resources for people to engage in various activities within their communities after regular work hours need to increase. As labor forms diversify nowadays, I think it’s crucial to develop diverse ways for people to balance contributing to society with their jobs, activism, and research. For example, during the emergency martial law period, YoonToiCheong operated as a part-time structure where designers, researchers, and activists collaborated on research and program planning. I also experienced the joy of working together by inviting friends I met in the square to host events, run programs, and participate in research.

7. In After the Square, I deeply resonated with the perspective that the square is not just a space for protests but a “living public sphere” where citizens actively engage in practice and dialogue. Do you think that the solidarity and connections formed this way can lead to sustained democratic practices even outside formal institutions?

I believe it is important both to create mechanisms that allow citizens’ opinions to be reflected in government policies and legislation, and to establish everyday public forums centered around local communities where citizens can comfortably participate.

For example, in Korea, there are governance structures such as the “Youth Policy Coordination Committee” that allow young people to participate in policy discussions. However, young people are not yet empowered to lead public discourse on social agendas or granted meaningful authority. In Europe, each EU member country operates national youth councils, and alongside non-governmental youth organizations, they run the European Youth Forum. The EU officially recognizes the European Youth Forum as a partner and legally mandates the creation of formal consultative bodies to develop youth-related policies and cooperation frameworks.

As various social agendas arise during this transitional period—such as digital transformation, climate crisis, and demographic changes—the youth generation inevitably bears the greatest impact. It is crucial to empower young people as stakeholders with responsibilities and authority to actively participate in policy-making processes, publicize new social agendas, and lead change.

At the same time, beyond formal institutional settings, citizens should be able to naturally meet and interact to sustain everyday public forums. Many youths who joined protests for the first time in this recent square have developed interest in new social issues. Some have expressed that they lack people to talk about politics or social matters in their daily lives. Therefore, more spaces are needed where people can gather based on shared interests or concerns within local communities and engage in dialogue.

8. During the process of writing the book, were there any perspectives or passages from the other authors that particularly impressed you? If so, please share them.

First, in Professor Shin Jin-wook’s section, what stood out to me was the approach of not viewing the so-called ‘far-right’ as a homogeneous group but rather classifying it into various layers based on the degree of extremity, and considering different responses tailored to each layer. I believe that practically designing and devising strategies based on this nuanced understanding will be a crucial task for Korean society going forward. He posed very valuable questions that my colleagues and I will need to ponder.

In Professor Yang Seung-hoon’s part, I was particularly struck by his perspective. He cautioned against simply labeling 2030 men as conservative, instead seeing them as a fluid swing voter group and interpreting their stance as accumulated anger toward progressive political forces. While I don’t fully agree with all points in the essay, reading it critically made me reflect on the absence of meaningful political representation for youth in Korea’s current political landscape, and sparked my imagination about what discussions are needed to create new political spaces in the future.

Professor Lee Seung-yoon’s section was interesting for presenting cases on political participation patterns among precarious workers. Traditional labor forms are dissolving in Korea, and more workers are now in diverse employment statuses such as platform workers or special employment types. Even the much-discussed K-culture workers are engaged in highly fragmented labor. There are also many unemployed youth simply categorized as ‘just resting.’ While I sometimes felt pessimistic about this, learning that globally the expansion of precarious labor groups has also fueled new social movements gave me hope. It helped me imagine what forms of social activism might be possible in Korea’s current reality.

9. What should the next square look like, and what role do you think young people should play in it?

When I think about what set this recent public square apart, I’m reminded not only of the shimmering cheering sticks and the creative flags, but also of the “Equality Guidelines.” At this square, we created rules that emphasized everyone’s equal right to participate in the assembly, and before the gatherings began, we would read these rules together. It was a collective pledge—by both organizers and participants—to ensure that this space would be safe and equal for all.

Of course, we can’t say these efforts were perfectly upheld, but the fact that such efforts were made at all is meaningful and worth commemorating. In fact, a politician who violated these rules was publicly criticized and even issued an apology. I believe that such culture will become the basic norm of future public assemblies. I don’t think we’ll regress from here—if anything, we’ll move forward. Activists and citizens who experienced the 2024–2025 assemblies and gained hands-on knowledge will continue to be active in society. And I believe young people will be at the center, setting new standards in line with the sensibilities of the times and leading cultural change.

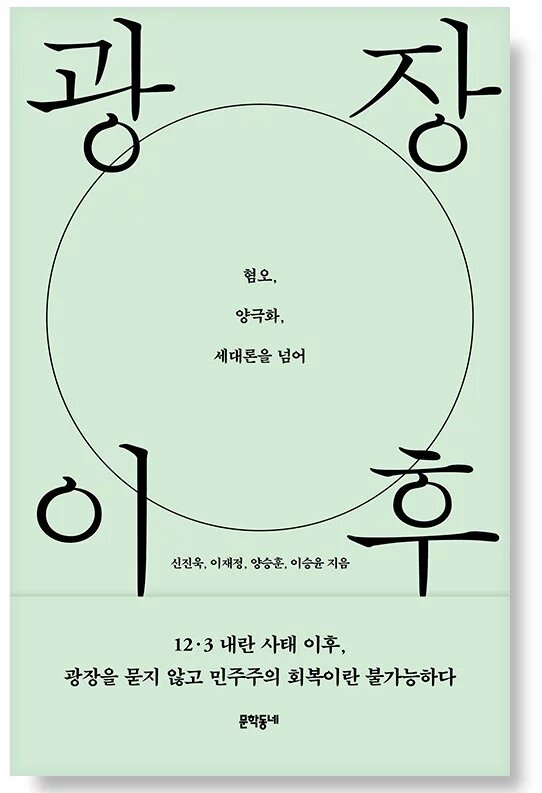

See detailed information about the book After the Square